Back in 2022, Jim Coe and I led a small research team with Sonia Long and Katie Chandler-Clarke, commissioned by a large group of funders to explore routes to power and influence for UK women’s organisations. We took a movement ecology approach to the work, developed from my previous research. Its taken a long time to find space to share the findings (a combination of heavy workload and a long sabbatical which I’m taking a little break from) but I’m finally writing this to explore some of the headlines I think are most interesting and still relevant.

A lot has obviously happened in the past year or so, but the need for organised Feminism and a strong women’s movement remains. Many of the issues flagged in the research report are yet to be meaningfully addressed, although I know funders have taken forwards some of the recommendations (you can read the commissioning funders response to the work at the start of the report). The women’s movement itself continues to toxically polarise around trans rights and sex work. At the same time a conservative / progressive ideology gap is opening up between young men and women around the world, seemingly galvanised by the #MeToo movement but extending to racial justice, migration, and the rise of the far right. Because Feminism is intimately connected to multiple other struggles, our findings are relevant far beyond the women’s sector to all movements for liberation and justice.

Research aims and method

The research assessed the national, regional and local infrastructure serving the women’s voluntary and community sector, and the routes available to power and influence for small / grassroots women’s organisations. We conducted 57 interviews with women’s organisations across different UK nations and regions, including mini reviews of the migration sector and violence against women and girls (VAWG) sub-sector for comparison. We workshopped findings and potential recommendations with the commissioning funders and a selection of interviewees.

How connected is the women’s sector?

Organisations delivering services tend to be locally hyper connected – for example through effective referral networks to supporting services. But these networks are not well connected to regional, national or UK wide actors, with especially notable gaps for power building or change making work. This means that the voices of grassroots women’s groups are often not being heard, and bigger organisations are often not grounding national campaigning and influencing in community demands. Those operating across devolved nations are better networked for influencing and service delivery than those across England, but connections between nations are weak.

At every level, women’s organisations are in competition for scarce funding, which understandably introduces tension and can act as a barrier to building stronger more collaborative relationships. We found only patchy connection between women’s organisations and wider social movements, through a handful of coalitions, and that the wider voluntary sector is generally bad at introducing gendered power analysis to its work.

Who has power in the sector and the movement?

One complaint we heard repeated by interviewees was that within the women’s sector, power is concentrated in bigger organisations which are invariably led by white, able-bodied, middle-class women. This concentration of power means bigger organisations are more able to access the sectors’ limited funding, including funding intended to support racially and other minoritised and disadvantaged communities. The effect is that smaller organisations led by those minoritised communities often miss out on funding for work that should be rooted in their lived experience. These power imbalances are bolstered through longstanding interpersonal connections between those running larger women’s organisations, across their senior teams, and externally with decision makers.

We heard that across multiple intersectional oppressions, including race/racism, disability and class, those with lived experience do not feel they are listened to by more powerful movement actors. The people most affected by issues are often not being well involved in changemaking attempts to solve those issues.

“Women without a real understanding of our needs are speaking for us”.

Interviewee in ‘Routes to Power and Influence‘ p22

Aside from the internal sectoral dysfunction, the people with most power over the women’s sector sit outside it – the (mainly male) commissioners of services, policymakers, politicians and others who hold decision making power over the lives of women, and who constrain the space in which women’s organisations can operate.

The role of funding

The women’s sector is chronically underfunded and has been for decades. The bulk of its funding comes from local authorities and Government departments through tendering processes for women’s services. These are renewed every few years, pushing organisations into fierce competition to lower their costs. Since this funding is coming from sources adjacent to decision makers, such funding also acts as a disincentive to engage in campaigning or even advocacy work. We heard many times that organisations were reluctant to ‘bite the hand that feeds them’.

On top of this, many community organisations we spoke with were kept busy firefighting immediate crises to cover their own core costs, keep afloat, and support women in their communities. So much so that they struggled to find any time for bigger picture analysis, advocacy, campaigning or power building work, however much they might want to do this.

What issues are women in the UK facing?

The most significant issues we heard about were poverty, gender based violence and abuse, and lack of access to affordable childcare – but there were many, many more and they are deeply interconnected. Lack of affordable childcare means women struggle to find work, impacting on poverty, impacting on housing, mental health and so on. Underlying these issues, women are disadvantaged by our societal systems both by the demographics of those holding power and by the way the systems operate, from Government to police and other statutory services. Sitting beneath that is the misogynistic and racist culture which informs norms, attitudes and behaviour in the UK. Patriarchy deeply affects our systems and institutions, and the way people relate to each other.

What is the women’s sector / movement achieving?

At the UK level, those we interviewed were fairly unanimous in agreeing that the women’s voluntary and community sector had not been recently successful in achieving change, although we heard a few good examples of legal and policy wins which stopped things getting worse than they are already, as well as a few smaller incremental wins. Generally the sector’s energy was focused on firefighting policies which would further erode rights and livelihoods, with limited success.

Many interviewees spoke about the relative success of efforts to tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG), with some positive mentions of the coalition to End Violence Against Women. But even considering the strength of this sub-section of the wider sector, people felt the progress they would like to see on gender based violence and abuse wasn’t there.

Most change focused efforts are being made through policy and advocacy work. These efforts are achieving a limited impact in the tough context of Westminster, but we heard some examples of success at local levels and in the devolved nations.

Is the women’s movement directing energy into the most effective approaches to change making?

A healthy movement ecology normally encompasses a wide variety of approaches to making change, to challenge and shift power at different levels. In the women’s movement little attention is given to organising, meaning strategies that focus on fostering leadership and building agency of women with lived experience so they are able to self-advocate and step into their own power are lacking. Activism and even shallow public campaigning similarly appear to be under represented in the women’s space. While we heard some good examples of media/social media campaigning to challenge dominant narratives, there is room for more work in this area.

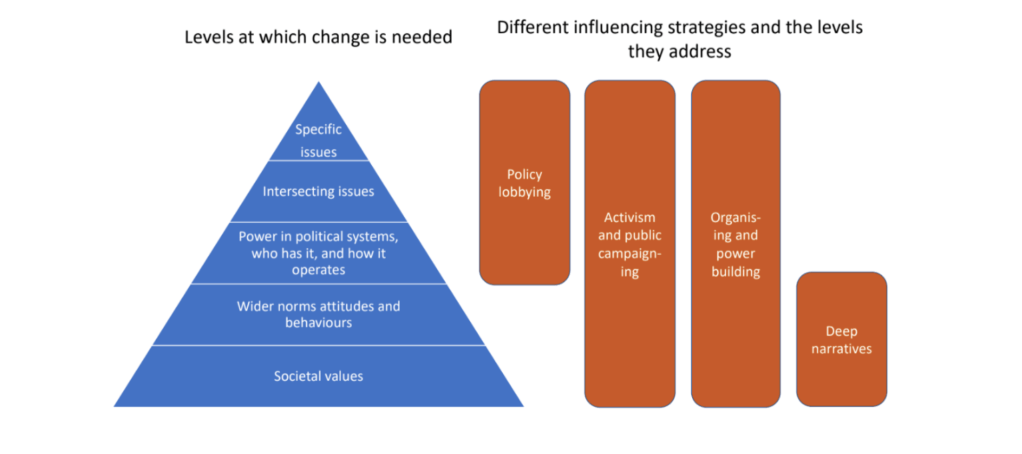

While policy work is cheaper to fund and often short term in scope, as illustrated by my collaborator Jim Coe in the diagram below, it is only effective in addressing surface issues, and to a limited extent the more obvious wielding and operation of power in systems. Investment in publicly engaged campaigning, organising and power building, is needed to address the norms, attitudes, behaviours and societal values which fuel the more surface problems. Such work is slow and resource intensive, but over time could help shift the policy space and make transformational progress, rather than chipping away to prevent regression on issues.

Polarisation and conflict

“It doesn’t feel like there’s a ‘women’s movement’ because there are lots of different agendas and different analyses happening, and not much cohesion”.

Interviewee in ‘Routes to Power and Influence‘ p33

Most of our interviewees did not feel part of a wider movement beyond their own immediate community, and some spoke about the absence or fragmentation of the wider women’s movement. When this research was conducted in mid 2022, we found that conflicts around issues of trans rights and sex work were causing destructive divides across the sector. Polarisation around trans rights was the most toxic of these conflicts, and it appears that these have only deepened since. Many interviewees commented to the effect that conversations around this were “incredibly destructive … toxic and difficult” and “sucking the oxygen out of these issues”. We were repeatedly told that “People have lists of organisations who agree and disagree with them and don’t work with the others”.

Connected to these conflicts, we found a split between grassroots groups (who tend to be younger 3rd and 4th wave Feminists) and professional services (mostly run by older second wave Feminists), who have different views on key topics such as decriminalisation of sex work and trans inclusion. This is contributing to a lack of connection and some hostility between two key parts of the women’s movement.

It’s hard to know what to do to resolve these entrenched conflicts, but they are sucking energy away from other important women’s issues whilst eroding the rights and well-being of trans women and sex workers.

Recommendations for funders

Since the report was aimed at its commissioning funders, there are plenty of recommendations for anyone disbursing funding in the women’s sector and beyond. Here are a few of the most important:

- Invest in power building through organising and public campaigning.

- Ensure funding pots are accessible to smaller and unconstituted organisations and groups.

- Consider focusing work locally to build networks of influence.

- Expand trust based, unrestricted and long term funding, with minimal application and reporting processes.

- Establish pooled funds in which decisions are made by leaders with lived experience

- Create spaces and processes to air and resolve movement conflicts.

Recommendations for all social movement actors

- Make time to foster relationships with others across the sector. Relationships are strategy – they’re the foundation for collaboration and power building. Look for opportunities to connect across difference, network, and build common goals.

- Map your movement, assess your role in the movement ecology, and consider adapting your work to increase the power of the movement as a whole. Is there enough organising happening to build power? Is activism / direct action strong enough to grab headlines and attention to push your issues forwards? If you’re not in the best position to deliver what is missing, consider how you can best support others who are well placed to do this, for example through partnership work or even through incubation of new organisations.

- If you work for a big NGO, prioritise centring the voices of those most affected by the issues you’re working on. It’s not easy to connect with marginalised communities but it is essential work if we want to truly win big and change things. Tips on how to do this can be found in my previous writing Can grassroots groups genuinely partner with NGOs?

- Bring more women of colour, disabled and working-class women to internal positions of power in your organisations and governance. As well as partnering with communities, you should entrust them with positions of leadership in your own organisation.

As always, I welcome your thoughts on all of this – please start a discussion in comments below or find me on Twitter or Linkedin.

If you’ve enjoyed my writing & would like to support me to create and share more you can buy me a coffee. I share my work for the love, in the hope that its useful to strengthen movements, and that’s the biggest reward. But if you feel moved to donate something (no pressure at all) it would be gratefully received.

Thanks for this thought-provoking article. You make some very valid points, some of which I’d like to highlight and respond to. As the CEO of Women’s Resource Centre, whose role is to promote the invaluable and often life-saving work of women’s organisations, your blog raises some pertinent issues in terms of our own strategic thinking regarding what our sector requires and needs to do.

It’s true that the women’s sector has not been able to have as much impact as it would have liked in terms of shifting the dial on fundamental improvements in women’s lives in recent years – no equity group has. Everything has gotten worse for all marginalised people in the UK. I think perhaps our points of emphasis for why this is might differ. The polarisation within the women’s sector on certain issues – while it certainly does exist – I think is over-emphasised in your post. The broader context for this lack of overall progress for women has been the wider social and political context (which you do also briefly mention): a government that is hostile to our messages and demands, the implementation of austerity measures, never-ending cuts and the ongoing impacts of the cost-of-living crisis. These events – and the subsequent lack of funding – have, I think, totally overshadowed our internal differences in terms of our abilities to push a more progressive agenda.

You rightly mention, “Sitting beneath that [the government, police, statutory services] a [sic] the misogynistic and racist culture which informs norms, attitudes and behaviour in the UK.” You hit the nail on the head when you identify these structural and systemic problems that are massive barriers to pushing women’s equality through a stronger women’s sector. But your post seems to imply that it is the sector’s own self-sabotage that is a big hindrance to tackling these, which I don’t think is correct.

You talk about the importance of organising, collective voice and campaigning work and I would totally agree. The main problem is that funders rarely fund this work. Specifically, during and since the pandemic, when life has become so much worse for women, it has (understandably) fallen down the list of priorities as limited funds get directed more towards frontline services. But the women’s sector has never just been about ‘delivering services’ – promoting our feminist values has often meant being at the forefront of social change, so money for ‘collective voice’ work is desperately needed too, as are core costs to keep organisations going – which is less appealing to funders over time-limited or ‘innovative’ projects.

Like much of the VCS, the women’s sector has become professionalised over time, which has probably contributed more to a growing gap between organisations and the ‘feminist movement’. However, you’re right: collaboration within the sector can and should massively improve. Joint working is a no-brainer, yet competition amongst organisations—largely because of the funding structures and processes—makes this really difficult.

You identify the lack of leadership and the marginalisation of Black and other minoritised voices as internal problems too. I agree, which is why Women’s Resource Centre has been running its Feminist Leadership Programme for a number of years now, prioritising Black and minoritised applicants and organisations. We’ve also established the Network for Black Women Leaders, through which we are now delivering a popular coaching and mentoring programme alongside feminist leadership training.

We have helped set up the Alternative Women’s Economy (AWE) network in Manchester and the Greater Manchester Women’s Media Hub (GMWMH), where marginalised, low-income, working-class, Black and minoritised women can tell their stories, try and effect change through changing the media narrative and influence policymakers. This is in response to the fact that, as you say, larger (often white) organisations tend to lead on campaigns because they have the resources, but there are still attempts to try and bring in different voices in other parts of the sector. Many women’s organisations have signed up to the Anti-Racism Charter as a set of rules to encourage a more level playing field between bigger and smaller organisations when bidding for larger contracts, for example.

The development of local and regional networks, as you say, is also vitally important – but the painstaking, long-term nature of this work is rarely funded, and the outcomes might take many years and reformulations to become clear. One example is the Mama Health and Poverty Partnership (MHaPP), which you mention in your report as one of, “two fantastic networks of service-providing organisations in Manchester which connect with each other, providing interconnections for many small organisations.” But what is missing from the analysis is how this partnership came about, which is a key piece of the puzzle if you are analysing the sector ‘ecosystem’. It’s what funders should know when they’re thinking about how to fund strategically.

Partnerships do not come out of nowhere – they are usually the culmination of a hard, long-term effort, coordinated by impartial and trusted organisations that can bring women together, who aren’t competing for the same pots of money, who provide an infrastructure, guidance, and training etc. Women’s Resource Centre supported the development of the MHaPP for five years with a three-year grant from Smallwood Trust. Through WRC’s Women’s Commissioning Support Unit (WCSU, 2015-2018), a pilot project funded by Esme Fairbairn Foundation, we developed the strategic and delivery capacity of the women’s voluntary sector by establishing regional partnerships of women’s organisations in Greater Manchester, the Northeast, Cambridgeshire and the West Midlands. Two of these were partnerships of Black and minoritised women’s organisations, which remain in existence today. We need to be highlighting these connections to funders so that long-term, unglamorous infrastructure work is valued more highly. This project generated around £1.5 million for the organisations involved.

The London VAWG Consortium is also another excellent example of a model developed to counter the competitive commissioning models that pit bigger organisations against smaller ones and generic ones against specialist ones. Again, this didn’t just spring from nowhere, but we need to get better at promoting these partnerships to funders.

It would also be interesting to research more into why partnerships are so tricky to develop and grow, or why Black and minoritised organisations come to a brick wall in their ability to grow beyond a certain size… The question of what we all mean by ‘system change’, and how we get there is a debate that certainly needs to be had in more depth amongst us, too.

Thanks again for your contribution to furthering the debates within the sector. We all need more spaces like this to think strategically about what’s going on for our organisations and the women we support…

LikeLike

Thanks Vivienne for your thoughtful response to my post. In it I have drawn out headlines that I wanted to emphasise from the substantial piece of research its based on. I enjoyed talking to you back when we conducted this, so thanks again for your contribution. We’re in complete agreement that the context the women’s sector is operating in is extremely tough. It’s hard to say whether or not other equity movements have made more or less progress than the women’s movement without doing more work, but it’s certainly broadly true that it’s been a very challenging time for all equity and justice work.

One of the major purposes of the research and for sharing what I have was to encourage funding of collective voice, organising and campaigning work in the women’s sector, as well as greater networking, partnerships & connection from the grassroots up. Thanks for sharing some examples of your work.

In addition to all of the above, the polarisation and conflict I highlight was mentioned again and again as causing barriers to collaboration and draining valuable energy. It seems to me that since the research was conducted that has gotten worse rather than improved, but I’d love to hear if that’s not the case / about any work that has bridged this divide.

LikeLike

Just a few questions based upon the research you’ve done, do you think there is a way for the organisations that exclude trans women or that are against sex work could work with organisations that are truly inclusive of all women? Is there a way forward given this massive divide that as you’ve pointed out feels like it’s a divide between generations of feminists?

I keep seeing attempted to get inclusive organisations refunded simply because they include trans women. And it makes it seem like there’s a section of the women’s sector who are primarily focused on attacking inclusivity and focusing on attacking parts of the Equality Act. Of course, both of these are observations from someone who works in the 3rd sector but not directly in the women’s detector. Was there any truth to these outsider observations found in your research? If there is any truth to this, did you research show any way to move forward in a way that betters the women’s sector? Is there any way to make the sector more supportive as a whole of inclusivity?

LikeLike

I wish I could answer these questions! I don’t have any magic bullet suggestions sadly – this needs attention and work to find a way through. Some kind of conflict mediation process perhaps? I didn’t hear about organisations being defunded but I did hear about lots of organisations not working together because they couldn’t agree on whether or not trans women should be included as women.

LikeLike