In 2019 I explored youth led movements in two new pieces of research

Last year saw the rise of powerful movements led by young people, and at the same time a broader shift away from professionalised insider advocacy to a more outsider people-powered approach to creating change. As major governments around the world continue to lurch towards the authoritarian right, our movements are becoming more radical and hopeful, with young people playing a major role in driving this change.

Working with my friend and fellow consultant Jim Coe (host of the Advocacy Iceberg podcast), we published two pieces of research in 2019 exploring inspiring case studies and the wider landscape of youth led change in the UK. Below I share some headline learnings and reflect on what our findings might mean for us at the start of a brand new decade.

Report 1 – Learning from inspiring youth led campaigns

The first paper we produced can be read in full here: Youth Led Campaigns and Movements. It contains a series of in depth case studies with some analysis of cross cutting themes, and was commissioned to inspire and inform the launch of the Young Activist Network by MAP in Norfolk.

The case studies explore the historic work of the SNCC in the US civil rights movement, the Sunrise Movement behind the Green New Deal, March for our Lives, a history of school strikes in the UK from 1888 up to the current UKSCN led climate strikes, and the We Will mental health campaign in Cumbria.

There is much more detail in the full report, and the case studies were fascinating to research. Below I’ve pulled from the findings three key lessons for movements of all ages and the top three strengths of campaigns led by young people.

Lessons for movements of all ages

1. Issues are inter-related and complex

Having too simple an understanding of a problem, or its solution, can be a common pitfall – many campaigns focus on one limited issue which actually cannot be solved without giving attention to wider connected issues. The case studies we identified all acknowledged the complexity of the issues they’re facing, and structured their campaigns to try to address that complexity.

2. Distributed leadership is key to growing at scale

Offering opportunities to new supporters to step up to leadership can hugely increase the number of people involved, and therefore impact, far beyond what a core group of organisers could achieve alone. Campaigns that don’t offer this are likely to have limited engagement and scale.

3. It’s important to engage those most affected by the issue

People who come together because they have experience of an issue may not necessarily be representative of the wider community affected by it. Both the Parkland and Sunrise movements have invested in ensuring that more diverse voices are amplified and involved in the movements; this needs explicit attention to get right.

Three key strengths of campaigns run by young people

1. Speedy consensus decision making

Youth-led groups tend to be more accepting of fast paced consensus-based approaches than traditional adult-led organisations. Digital platforms facilitate this quicker and more nimble decision making, and young people who are the natural users of those platforms.

2. The moral authority of young people

When children and young people protest, it can attract significantly more public and media attention than when adults take similar actions. Part of this may be the novelty value, and the fact that it has been less usual until recently. But the moral authority of children and young people is incredibly powerful in getting media cut- through on issues they are directly impacted by. The Parkland students and Greta Thunberg are excellent recent examples of this.

3. Going beyond conventional ideas of what is possible

In all our case studies, the young people were not constrained by conventional ideas of what is considered ‘achievable’ as adults often are. Instead, the young people identified the change they sought, worked out what was needed to achieve that and pushed for it with full belief it was possible.

Report 2– Youth led change in the UK

The second report is a longer more detailed piece of research which can be downloaded here: Youth led change in the UK – Understanding the landscape and the opportunities. This was commissioned by The Blagrave Trust to inform their own strategic and investment decisions, and to encourage others to support and invest in youth led change.

The full report runs to 51 pages – I’d recommend reading it all as there’s so much more in there than my thoughts on the key headlines I summarise below.

Context

Sustainable change involves power, norms and policy

There standardised approach to achieving social change in the UK (and much of the global north), with set-piece, issue specific campaigns underpinned by expert research, is no longer working well. Achieving change is sometimes about specific policies and the direction of policy. But it can and should be more than that. Sustainable, systemic and transformational change comes through challenging power dynamics, redistributing power, and promoting social norms that open up space for more progressive action.

Leadership/ engagement by those with lived experience is increasingly valued

Many communities feel marginalised and disconnected from decision makers, who in turn show only limited receptivity to these groups. This makes it very hard for established NGOs to act as a bridge between the two in ways that can lead to meaningful change.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of leadership by people with lived experience of an issue or combination of issues in campaigning, to begin to turn this around. Despite massive resources (still) being locked up in the traditional NGO model, most of the interesting / impactful campaigning and activism is being pushed forward by a new wave of actors, engaging people affected by issues directly, at scale and in depth.

Big NGOs are struggling to adapt

While the social change sector is generally moving (at least rhetorically) from delivering change ‘on behalf of’ people towards operating in solidarity (if not actually being led by those most affected), it faces huge challenges. Historical decisions and organisational strategies wed many large organisations to outdated approaches that are proving resistant to change, and fundraising / brand considerations often act as further blocks.

Mapping youth led change in the UK

While we found plenty of youth engagement work, aimed at developing young people’s skills, confidence, knowledge etc, only a small number of organisations met our criteria for genuine youth leadership with an external change focus. The same organisations seemed to come up again and again, in the press, on panel discussions etc. For example, UKSCN, We Belong, and The Advocacy Academy have all received a lot of attention.

Despite this, large numbers of young people are engaging in activism. 16-24 year olds are the most likely group to have signed a petition or protested in the last year. We think there is huge potential to engage and support leadership of young people in change, but current support is patchy at best and limited in scope.

Pathways into activism

The number of young people moving into leadership roles in activism is currently

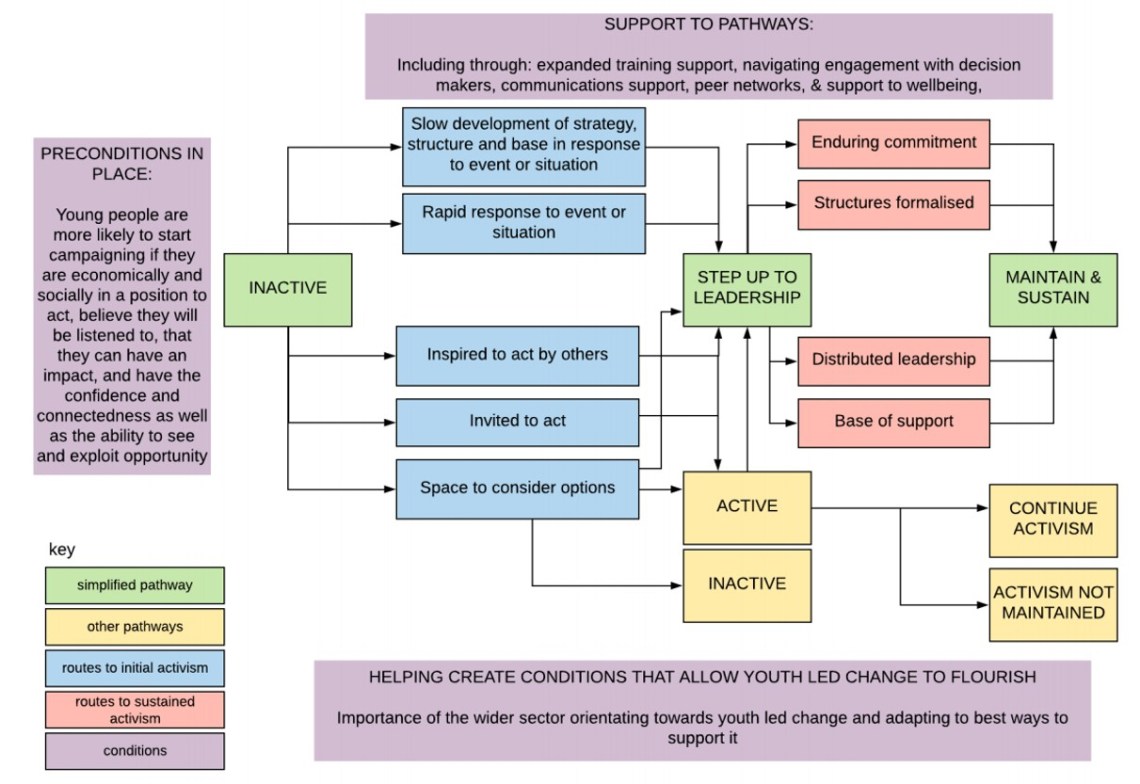

very small, but there appears to be significant potential to increase this. Based on what we read and heard, my colleague Jim Coe set out the generic routes that young people follow into activism in the diagram below:

As you can see, there are three points of intervention for funders or others looking to support youth led change, and the detailed recommendations in the report come from these. In summary they are:

1. Preconditions needed for young people to start to engage in the first place

Work here could include tackling the negative portrayal of young people in the media, bringing political education into schools, or work to tackle issues of poverty and marginalisation more widely.

2. Support to navigate the pathways; training, setting up peer networks etc

This could include supporting young people in the initial stages of their activism by helping to respond rapidly to issues, or to strategise; by promoting youth led change widely to help scale it; or making space for young people to consider issues affecting them / how they might take action.

Then to help maintain and sustain that activism, there is need for shorter and more accessible trainings; for helping young people navigate relationships with decision makers; for giving guidance around sharing personal stories; developing peer networks, and supporting well-being.

3. Helping create wider conditions to allow youth led change to flourish

Firstly, there is a need for re-orientation of the whole social change sector towards young people in order to engage them.

For funders wanting to give money and support to young people, they need to do more than apply current models of funding for established adult organisations and distributing funds to different groups. This could mean more pro-active outreach, embracing risk, focusing more on long term change and being less prescriptive around reporting.

No hub or umbrella body exists to connect actors, foster learning or share information, either in social change more broadly or youth change specifically – so that’s a gap that would be well worth filling.

If funders are genuinely interested in youth led change, the natural end point of such exploration would be to give power over funding and funding strategy decisions to a cohort of young people leading change themselves. This is modelled in participatory grant making by the Edge Fund in the UK, and various other projects in the Edge Funders Alliance across Europe.

Key takeaways

So what does all this mean? As we enter a new decade with a right wing Conservative majority government, progressives working for social change are facing some serious challenges. We need the energy and fresh thinking of young people concerned about climate change and fed up with the current status quo to help drive things forward.

Young people are passionate about making change. They are the most progressive age demographic, and have the time and energy to put in. Their fresh thinking can push beyond the small wins ‘professionals’ identify as achievable, to re-imagine and ultimately transform the world.

Funders interested in youth development and campaigning would do well to consider our recommendations around funding youth led change, ideally working with others to scale up interventions.

Big NGOs should seriously consider re-orienting campaigns (and supporting campaigns they are not running directly) to distribute leadership to young people, to help scale and energise movements.

Grassroots groups would benefit from making their work much more accessible to young people and offering pathways to leadership.

1 Comment