US organising scholar Dr Hahrie Han has a new book out, Undivided – The Quest for Racial Solidarity in an American Church. It’s her first more mainstream offering, using storytelling rather than academic analysis to present her research. In celebration of this, and in partnership with the incredible Act Build Change, Hahrie returned to London for a mini tour almost nine years after Tom Baker (aka The Thoughtful Campaigner) and I bought her over, back when organising was poorly understood and little practiced in the UK.

Below I share my reflections on the food for thought Hahrie provides in her book and the three events I attended in November 2024. I am writing this to make the argument that these organising insights are precisely what is most needed to respond to this political moment, characterized by the continued rise of the right and the challenges of polycrises – ‘a time of monsters‘.

Who is Dr Hahrie Han?

Dr Han is a political scientist from the US. She is a professor at John Hopkins University, where she founded the P3 Research Lab, which examines the way civic and political organisations make the participation of ordinary people Possible, Probable, and Powerful (the three P’s). Her book How Organizations Develop Activists has been hugely influential in popularising organising approaches in the UK and around the world. Such approaches focus on building the collective agency and relational power of communities in order to achieve change, in contrast with the shallower public engagement of mobilising approaches, which until recently had come to dominate campaigning efforts (often through digital ‘clicktivist’ tools).

Hahrie also collaborated with Elizabeth McKenna and Michelle Oyakawa on Prisms of the People, a book exploring how movement organisations can transform participation into power – some of the findings are summarised in this report on understanding and measuring people power from the P3 Lab. There’s a lot to learn in this material and I hope to write more about it soon, perhaps alongside an online training with Hahrie herself – watch this space!

A time of monsters

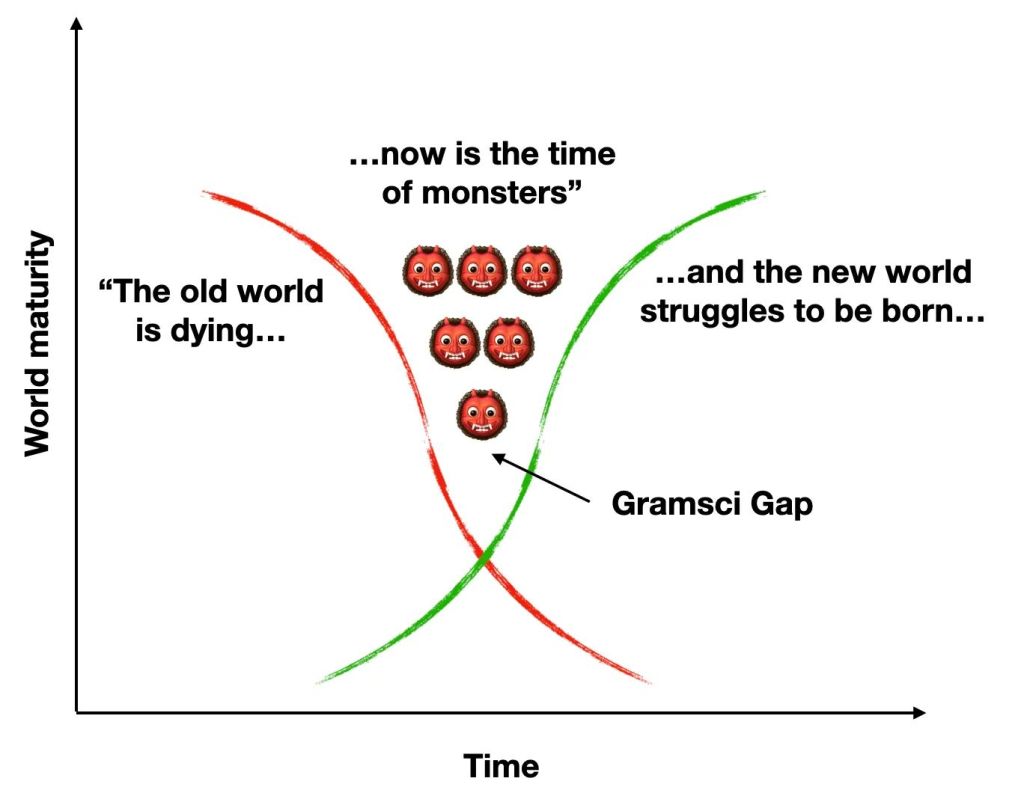

“The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born – now is the time of monsters” Gramsci

I wanted to refer to the current political moment we find ourselves in (thanks to Venkatesh Rao for the above illustration) – with Trump getting sworn in for his second term as US president, and the continued rise of the right around the world. It seems as though authoritarianism is getting ahead in the race to replace neoliberalism. But this new world order is far from fixed or stable. New actors are appearing, coalitions and alliances are forming, previously de-mobilised folks are re-mobilising and re-shaping the playing field. I think we still have everything to play for, but we need to be smart about power. How do we build viable alternatives to the right leaning hegemony we’re seeing come together?

Back in 2019 I developed a power mapping tool based on Gramsci’s ideas around hegemony with academic and activist colleagues from Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain and Australia. It’s a tangent to this piece but worth reading more about this if you’re interested in an alternative look at macro power relations to inform social change strategy, as existing alliances fracture and a new hegemony tries to form.

But what I wanted to share in the bulk of this piece is that organising, providing opportunities for genuine participation in civic and political life, offers many of the answers to resist the right and build new forms of power. If you’re interested in much more detail on how to implement this in party political organising, check out the excellent e-book by Ned Howey which I helped to edit: The Age of Junk Politics. The insights on organising below could equally apply to any social change efforts working to shift power, outside and inside political parties.

People want to get involved with politics and in communities but there are no meaningful opportunities

Hahrie Han talks about there being a supply side problem, not a demand issue, in terms of participation in politics and civic life, and in commmunity. People do actively want to get involved but they’re just not provided with meaningful opportunities to change things. It’s a situation playing out in both politics and social movements, where we see a serious mismatch between what people want and what people are offered. Less and less people are actually voting in elections, and the number of voters no longer aligned with either of the main parties in the US and UK is growing. People are hungry for something that dominant political parties are not providing. At the same time, people aren’t desperate to find their community engagement in a political space, unless we made it inviting.

In the UK, we’re seeing Reform step squarely into that offer, organising in communities where people are most dissatisfied with the status quo. They offer a mixture of populist policies speaking to the things people are really worried about (like NHS waiting times and the lack of affordable housing), whilst punching down on minorities (like people who have migrated to the UK) who they blame for the systemic failures at the root of these problems. I’m hearing lots of folks discussing this across the social change space, but very few actually investing in organising for an alternative (with a few notable exceptions like Hope Not Hate).

Moving politics, and movements, from spectacle to practice

The way we commonly engage people in social transformation through movements or political parties is individualistic and transactional. We assume people have fixed identities, needs and beliefs and offer them transactional engagement opportunities based on these, with minimal agency and without acknowledging the possibility that meaningful engagement can actually change people. Inside this model there are no opportunities for people to grow through participation, develop relationships across difference with people they wouldn’t normally meet, to learn, or to fail. The siloes so obvious on social media bleed into every part of our lives, deepening othering and division across increasingly intractable conflicts.

Hahrie Han suggests that when movement and political engagement is actually grounded in practice, identities can be related to as experiences rather than fixed categories. In this way, when we’re organising, participation means negotiation across these identity experiences, through understanding each others perspectives, making collective action across difference possible.

“We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.” Robert Jones Jr (commonly misattributed to James Baldwin)

The quote above is shared all over the internet as a battle cry for people to protect themselves from engaging with people that hate them (or more commonly, people that they see as being opposed to and harmful to people with their identities). While I can very much understand why this is, and wouldn’t advocate for people directly affected by issues to be leading attempts to change the minds of those perpetuating harms against them, I am sympathetic to Hahrie Han’s suggestion at one of her book tour events that this quote is commonly weaponised in a way that perpetuates division.

In ‘Undivided’, the anti-racist programme in the US mega church Han’s latest book describes, they started out by engaging people in small groups with equal numbers of black and white participants. While later iterations of the programme recognised that this format created an unfair burden by having people of colour explain racism to their white counterparts and changed this, that engagement across experience was very powerful.

Belonging before belief

One of the key learnings of Han’s book ‘Undivided’ is the motto of the church the programme is set within – the value of ‘belonging before belief’. The church invites people into a space of radical belonging whether or not they believe in God or identify as Christians to begin with. By offering belonging, people feel welcome and are invited into small group configurations where they are able to develop relationships and form communities (sharing food, visiting each others houses, celebrating together). In this way, people are invited to engage through relationships, and often end up starting to identify as Christian. I have noticed something very similar happening in the Buddhist order I am part of, where small groups invite people into belonging and deeper relationship through courses and Dharma study.

These principles equally apply to efforts in social change organising. Han describes the formation of small groups as ‘honeycombs’, comprised of small cells which can cohere powerfully together en masse while being held in place with a small number of committed, personal relationships. These spaces of intimate connection foster deeply accountable relationships with commitment to each other. In the trusted space of deep relationships we can tackle deep societal oppressions, by understanding each others experiences and the impact beliefs, ideology and actions have on others. In this way, well designed organising is able to cultivate spaces which allow for transformations in belief, understanding and action.

But this is precisely the opposite of identity based activist culture. When we begin from ideology and belief, while this can offer valuable healing caucus space, for wider social action it means you only attract others like you, who already agree. It doesn’t enable us to engage with and transform those who wouldn’t naturally be in agreement. We need transformation and engagement to build better alliances and new power to steer us through this time of monsters into something new and better. I’m not suggesting this should be led by those most affected by oppression and injustice, and we’re unlikely to win over those most firmly in opposition, but many in between are alienated by the existing polarisation, and could be engaged through personal relationships. Through organising.

Building strategic capacity

Han argues that the sticky problems we face are de-centralised – racism appears across society from school exclusions to workplace micro aggressions. The climate crisis is affecting homes, businesses, food systems. Similarly our solutions must also be de-centralised, led by people able to make decisions autonomously about how to respond.

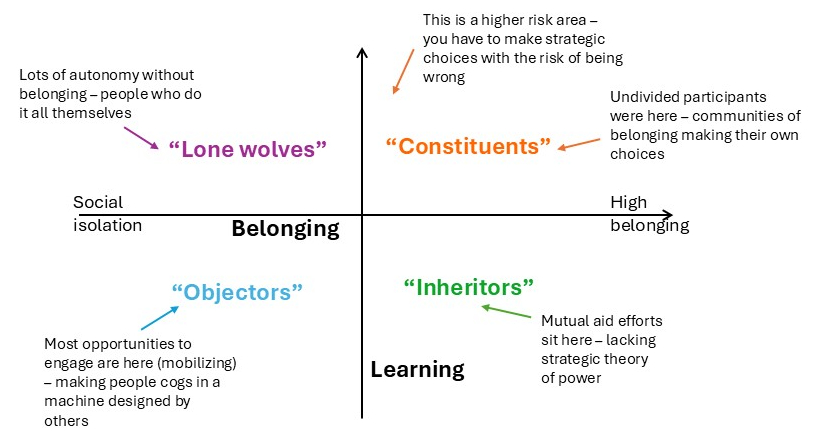

This building of strategic capacity means building individual and collective agency, and can’t be done by mobilising people to do something. When NGOs, unions and parties set strategy centrally and develop small actions for people to take, those they engage don’t have any skin in the game and cannot learn from mistakes. Just giving simple actions like signing petitions enforces a feeling that people are cogs in a machine (see the lower left quadrant in the diagram below – where most commonly offered social change actions from NGOs and others sit).

Instead of mobilising people to ‘do a thing’, Han argues the focus needs to be change to equipping people to be able do what is needed to be done (see the upper right quadrant of the diagram below). This way people can, in community, decide how to respond to the challenges they are facing, take the risk of failing and learn and grow from those failures.

Designing organising programmes – maximising opportunities for learning and community

Following the money – the case for membership funding

Finally I wanted to take a moment to reflect on money and accountability. In Prisms of the People, Dr Han and her colleagues identified that the ability of marginalised communities to build power correlated with their accountability to a membership base. This means that the people calling the shots were members of the organisations, directly affected by the issues they were working on. Instead of ‘sign off’ and decision making flowing up to a senior management team and an external board, and often further upwards to funders, power building is most effective when it flows down to the membership.

This was one of the tensions identified in Civic Power Fund’s Power Up report, exploring organising in big charities. Charity structures are set up to lead and develop strategy from central expertise, lending themselves to mobilising approaches which can be agreed from the top, whereas in effective organising accountability flows in the opposite direction. I often suggest that charities looking to invest in organising consider how to navgiate such tension, for example by setting up organising projects as autonomous from central power structures, perhaps in an arms length organisation which the NGO can incubate.

Act Build Change recently released the Collecting Our Dues report, calling for a re-think around funding for organising, and challenging the popular belief that people can’t organise their own money / won’t give to organisations they value representing them. Its definitely worth considering setting up organising programmes to be funded this way, and also how money from philanthropic funders can support such a transition, to build power in the most effective way.

What might all this mean for social change makers?

We can’t all do everything, and organsing is clearly not for everyone. I’m not suggesting that all the other theories of change operating in social movements are not valuable. But we certainly have much less organising in our movements than we need to build the alternative power blocks we need to reclaim our future from the authoritarian right. If we agree this is needed, we need to make it happen.

- NGOs – Can you invest in organising? Support the organising that is already happening around your issue? Share power and resources, and collaborate, with grassroots groups and communities?

- Unions – Can you organise beyond your workforce, in communities? Can you shift decision making to membership in more agile ways? Can you foster greater connection and engagement through small groups?

- Organisers – Are there any tips here that could strengthen your work? How could you take it to greater scale?

- Funders – Can you invest in organising? The Civic Power Fund can help with this if you want some advice or don’t know where to start. If you are investing, consider how you can support accountability to flow down to membership rather than upwards to you.

Finally I wanted to share a quick plug for Act Build Change’s new membership offer. If you’re wanting to move into organising, or to improve your organising, their training is an excellent place to start!

As ever, I’d love to hear your thoughts – please comment below or continue the conversation on Linked In or Bluesky.

If you’ve enjoyed my writing & would like to support me to create and share more you can buy me a coffee. I share my work for the love, in the hope that its useful to strengthen movements, and that’s the biggest reward. But if you feel moved to donate something (no pressure at all) it would be gratefully received.